Education

Education was key in the narratives of the first generation of migrants who were born in Beloit or brought there as children. The schools formed a basis for the adolescents of this new generation to develop meaningful relationships with their peers. Some had their first school experience in schools in the South that closed during harvest season, and others attended school for the first time in Beloit. In addition to the classroom setting, schools in Beloit offered extracurriculars like sports and music that had been underfunded or absent in schools in the South.

In his oral history, Ersey Edmond, who moved to Beloit from Mississippi when he was in elementary school, remarked: “Schools were a lot better [in Beloit than Mississippi]—you learned a lot more.” Mr. Edmond had a meaningful experience being tutored outside of school hours when he first arrived in Beloit. Others, like Beverly Bond, spoke of how the extracurriculars, in her case playing clarinet in the high school band, provided some of her fondest memories of Beloit.

Race and Education

The connection between race and education in Beloit is varied. Children of migrants who attended school in Beloit have very different recollections of their experience than adults who were employed or involved in the field. Grant Peter Lee Gordon’s line of the Gordon family has something of a legacy in education. Grant Peter Lee Gordon was an educator in Houston, Mississippi prior to the family’s journey North, but failed to find work as a teacher in Beloit, presumably because of race.

His daughter, Louise Gordon Rhodes, faced similar discrimination in the Beloit school district. Rhodes was well qualified with a BS in Education from the Milwaukee State Teachers College and Master’s in Education from Atlanta University, where she took courses from WEB Du Bois and Langston Hughes. She spent her career teaching in Milwaukee, though Beloit was her preferred location. Of his father’s and sister’s experience with the Beloit school district, Ambrose Gordon said in 1976, “The idea was not accepted at all by the school authorities and even as late as 1935, when [my] sister was prepared through schooling to teach, the opportunity was not available to her in Beloit” (Ambrose Gordon Interview, 1976).

Ambrose Gordon was never directly involved as a teacher, but he did serve on the South Beloit Board of Education between 1964 and 1967. Based on these recollections, racial discrimination was very much a factor in hiring teachers in Beloit during the first half of the 20th century.

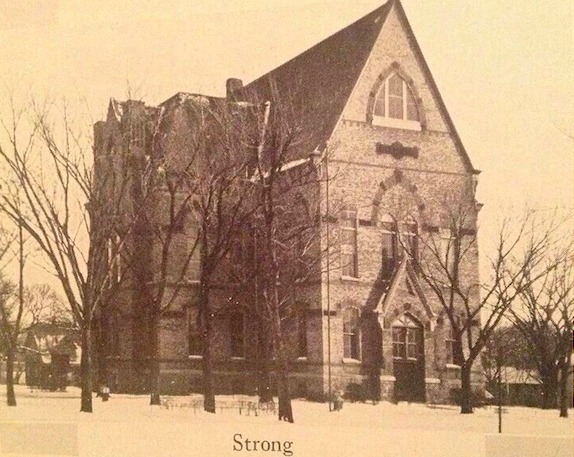

The treatment of Black students in Beloit schools in the early 20th century was different in primary school than it was in high school. In a 1976 interview, Sadie Bell looked back fondly on her experience at Strong Elementary School. "I think that we had a very nice schooling at Strong School; we never had any problems. Everybody got along fine, and, we all were very happy there." (Sadie Bell Interview, 1976) When she started first grade at Strong School in 1914, and all of the teachers at that time were white, and the school was integrated. When asked if she recalled experiencing any discrimination at Strong School, she replied:

"No, I really don't. And I, at that time, you'd be surprised. I think that they got along better than they do now, really and truly, I think that we were all treated the same in the Strong School area, and I never remember having any problems at all at the schools. The kids played together, and things like that, so I really don't remember any discrimination that would hit us, to make us notice it, and make us, we were so innocent we couldn't notice it really too. That could be." (Sadie Bell Interview, 1976)

She also noted that everyone was disciplined in the same manner by teachers, regardless of race. Sadie described changing relationships with white friends during her time at Roosevelt Junior High. They would talk to her outside of school, but not in school. Sadie perceived that middle school was a time that her classmates were realizing that they were different from each other because of race. In high school, Sadie and her Black classmates experienced discouragement from their teachers about their career prospects. Many black students did not take classes for careers that they were not likely to have in Beloit.

"Some of them even said-some of the teachers said 'Why are you taking typing? Typing-You're not gonna be a type-you're [not] gonna be a secretary or-'. I mean, it was a kind of discouraging thing to [say to] the young people, and, here, they would, shy away from these courses because they thought 'Well, I'm not gonna use it. I'll never use it'." (Sadie Bell Interview, 1976)

In Sadie’s era, the 1930s, many Black students were resigned to the idea that the only jobs they could get in Beloit were in factory work or in cleaning. Black students who were able to afford college often left to get a degree in the hopes of getting a better job.